The end of hyperbole as we know it

Everything in excess is opposed by nature.

Hippocrates

Sometimes it seems that the health and fitness industry is hell-bent on turning itself into a cartoon. Outrageous claims are everywhere and extremism is the order of the day. Every weight-loss and athletic training program is declared to be “the ultimate.” Supplements, exercise machines and trainers are routinely advertised as “ferocious,” “insane,” “outrageous,” “alpha,” “maximum,” “mega,” “incredible” and “awesome.” Everything is bigger, faster, stronger and more scientific than everything else. Like the Lake Wobegon kids, everything and everyone in today’s health and fitness marketplace is somehow “above average.”

Most of the time, we can safely dismiss these claims as over-blown rhetoric, the familiar chest-thumping of primates looking to one-up the rest of the tribe or attract a better mate. Alternately, we might conclude that these hyperbolic boasts are merely practical strategies for survival in an increasingly crowded and over-heated marketplace; bigger claims attract greater attention and in turn, bigger sales.

But these exaggerated health and fitness claims are not neutral, nor are they harmless. In fact, they are outright violations of the very nature of health. Even worse, they send a dangerous message to people who desperately need a sense of balance and proportion in their lives. In short, health and fitness hyperbole is not healthy.

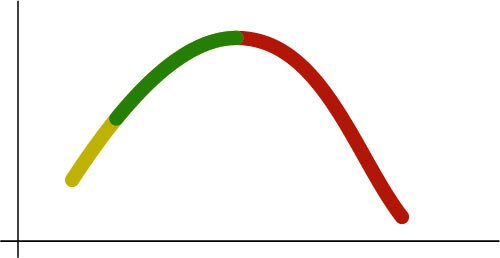

You don’t have to study physiology for very long before you discover that Goldilocks was right; there’s always a sweet spot between the extremes. Laboratory research and personal experience tell us that things that are beneficial in small amounts often become toxic in larger doses. Here we find ourselves drawn, again and again, to that iconic image of dose and response, the classic “inverse U” curve. Aristotle, Confucius and Lao Tzu would have instantly understood its meaning and its power. As the Buddha observed, the string on a musical instrument must be neither too tight or too loose.

We see it everywhere, both in the body and the natural world. There’s a period of increase in which a process builds on itself. Substances and efforts combine to produce a growth effect, a bounty or a payoff. This leads to a sweet spot of ideal or optimal function. Further increases in concentration or effort lead to diminishing returns as we approach a tipping point. This is followed by a reversal of the original benefit as the system begins to degenerate into illness and injury.

Today we find the inverse U in almost every encounter with life and living systems. We see it, for example, in our exposure to sunlight. At moderate levels, natural light is a powerful driver of Vitamin D production and has a profoundly beneficial effect on our mood and happiness. But beyond a certain point, these benefits begin to disappear, putting us at risk for heat stroke, dehydration and melanoma.

We see it the world of nutrition. Most nutrients follow the inverse U, with small amounts being beneficial, up to a tipping point. Protein, carbohydrates, red wine; beyond the sweet spot, substances that are nutritious in moderate amounts can become toxic. Even water.

We see it in the world of stress. When we’re under-stressed, memory, cognition and physical capacity are weak. If we add some pressure to the mix, we enter a domain called eustress and optimal function. But when we cross the tipping point, we enter into a world of distress, neurotoxicity, PTSD, sleep disruption, psycho-social disorders, immune dysfunction and disease.

We see it in the world of exercise. Vigorous movement is a powerful tonic for the entire mind-body-spirit, up to the tipping point. Once we cross over into the domain of over-training, exercise becomes a stressor and a health-negative.

We see it in the biomechanical properties of the human body. Every joint has an optimal range of motion. If that range is limited by tight muscles, tendons or ligaments, pain and injury are the result. But if the joint is hyper-mobile, it becomes vulnerable to dislocation and injury.

We see it in blood pressure, heart rate, blood sugar, hormone levels, neurotransmitter levels and every other dimension of our physiology. In fact, the inverse U curve is so common, we’d be hard-pressed to name any system or experience in biology or human life that doesn’t eventually turn back on itself. Sooner or later, everything runs its course, everything gets regulated by something else. In the world of health, extremism is almost always a vice.

The problem with hyperbole and exaggeration is that it leaves us with an illusion that we can defy the laws of physics, biology and even common sense. It suggests that by going to some sort of extreme, we can have a “breakthrough” to some higher level. But this is a dangerous illusion that does a disservice to our bodies, our clients and our culture. In reality, a breakthrough is more likely to become a breakdown.

Hyperbole is not a strategy or a training philosophy. Rather, it is an expression of fear, insecurity and inattention. It’s a reflection of our inability to live in the ambiguous present, with ourselves as we are. Ultimately, it’s our fear of death that drives us to claims of outrageousness and extremes of behavior.

But this sort of chronic envelope-pushing is doomed to fail; living on the right side of the inverse-U leaves us injured, diseased and frustrated, not to mention out of touch with the natural flux and flow of the natural world. Extremism puts everything at risk. As Gregory Bateson put it in Steps to an Ecology of Mind, “Lack of systemic wisdom is always punished. If you fight the ecology of a system, you lose–especially if you “win.”

Ultimately, health is about honoring and respecting the self-regulating nature of the systems that we inhabit. It’s a Middle Way, a Golden Mean. Balance and humility may not be sexy or lucrative, but they are consistent with the reality of our bodies and the world we live in. If you want to flourish, find the sweet spots.