Man does not live by food alone

Dateline 50,000 BC:

An epidemic of physical disease swept across the grassland of Southern Africa and the people were becoming sick and unhappy. Normally strong bodies grew weaker with each passing day. Hunters complained about a lack of vitality and their spirits were in chaos. Something was clearly wrong.

And so it was that the elders called for a gathering of the tribes. People came from all across the bioregion, walking long distances to reach a sacred ground at the confluence of two great rivers. Here they gathered, feasted, held ceremonies and danced. They called upon the spirits to visit their bodies and bring healing to the land. Then, when the moment was right, they sat in a circle and passed the talking stick from one to the next, each given a voice and an opportunity to be heard.

Opinions were many and varied widely. Some spoke of problems with the water and the food. Some said that it was the red berries that were making people sick and that things would get better in a new season. Others claimed that the weather was the source of their troubles and they must migrate to a new region to the north. Some spoke of signs that appeared in the behavior of animals and the movements of the night sky. Still others said that their spirits were out of alignment with the ancestors and that the shamans must intervene to create a new relationship with the world.

The conversation spanned several days and nights, voices and visions weaving together into a tapestry of deeper understanding. No final agreement was reached, but the elders returned to their tribes with a new set of ideas for reclaiming their vitality. In the days that followed, each tribe followed a different path, but all could hear the echoes of one another’s voices.

I recently returned home from the Ancestral Health Symposium 2012, held at Harvard Law School, August 9-11. Like last year, this was a powerful event with great enthusiasms, passionate opinions and excellent information. The organizers at the Ancestral Health Society deserve a big shout out for putting it all together. An event of this size is a huge undertaking with thousands of moving parts, hidden details and last-minute surprises. These people deserve our gratitude and our thanks.

That said, there were some notable weaknesses in the conference, just as there are in the modern Paleo movement as a whole. To put it bluntly, the modern Paleo movement is exceedingly narrow in scope. It is mostly about food, biochemistry and research presentations. In other words, it is not well-rounded. This point was neatly summed up in a post-conference blog post by Brandon Sewall at Primitive Movement “If this symposium is going to grow and influence, it needs range.”

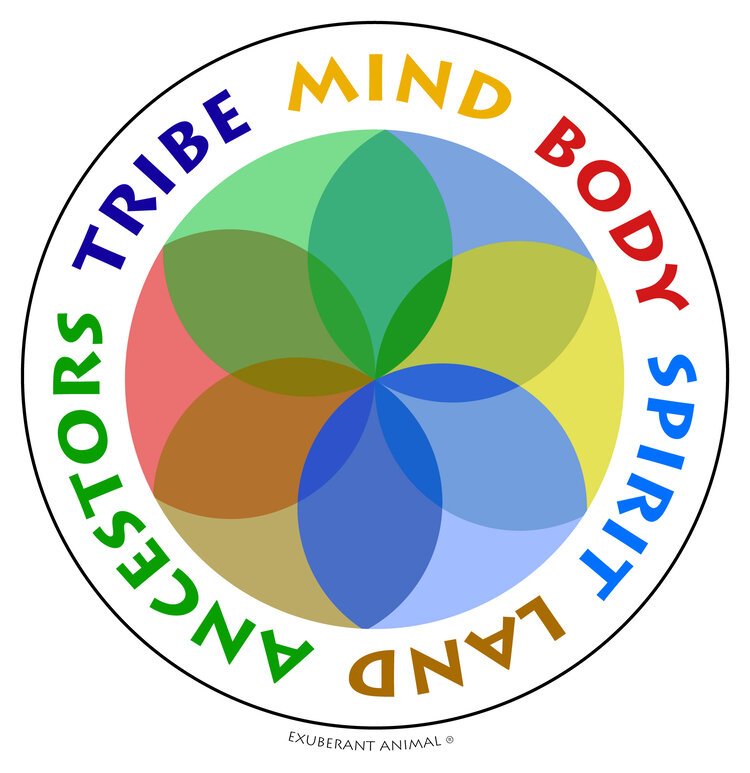

A comprehensive Paleo study would be a multi-faceted, multi-disciplinary process that integrates the totality of primal human experience. It would be both broad and deep, both classically academic and romantically creative. It would include both science and the humanities. It would include a vast range of studies, disciplines and arts. Paleo is about food, yes, but it’s also about exposure, the raw experience of living on the land, embedded in the natural world.

holismT

In this respect, the modern Paleo movement is not even close to being holistic. “Paleo” has become so tightly linked to diet that scarcely anything else enters the conversation. For most people, “Paleo" equals "Paleo diet.” Unfortunately, this one-dimensional focus eliminates a vast range of content and experience. In fact, our current obsession with food constitutes a kind of cognitive-cultural eating disorder: we have become “binge eaters,” gorging ourselves on food information while simultaneously ignoring most of the other qualities and experiences that contribute to a truly healthy, well-rounded life. Primal people would find our obsession with food to be incomprehensible and out of balance.

We get a feel for the state of the movement by noticing what we don’t see at AHS or on the typical Paleo blogs. For example, we don’t see native peoples or hear their perspective. We don’t hear much conversation about the body-habitat relationship. There’s not much talk about the hunting and gathering experience or about animal behavior. We don’t hear about sensation or the role of the nervous system. No one talks about bioregionalism, one of the most powerful concepts in the Paleo experience. Few people talk about our spiritual connection with the land or one another. Rarely do we see poetry, art, dance, dirt, sweat, emotion or blood.

To put it bluntly, the modern Paleo movement is simply too white. By this I don’t refer to skin color, although that well might be a valid claim. Rather, my point is that modern Paleo is too clean, too refined and too abstract. We have become so preoccupied with food, biochemistry and research ("My research can beat up your research!") that we are ignoring almost everything else. Our method has become too academic and Cartesian; AHS12 was a neck-up symposium about a whole-body, whole-life predicament. Ironically, the modern Paleo movement has become as refined as the white grains and sugars that we are so quick to demonize. If white food will kill us, so too will white thinking and white action.

With these considerations in mind, I hereby issue this challenge to the modern Paleo movement:

Make it more holistic. Make it more inclusive. Give it more breadth.

Take a chance on diversity. Open the doors to more views on the ancestral experience.

Give food a rest. Nutrition is a mature discipline; we now know most of what we need to know.

Invite more authentic Paleo voices into the circle, especially Native peoples, shamans, hunters and trackers.

Embody the vision. Include more movement, more sensation and more touch.

Above all, include more color, more blood, more sweat, more emotion and more dirt into the process.

In other words, put more Africa into it.