Inside out

As we all know, outdoor exercise is the way to go. Not only does it feel really good, a growing body of research now demonstrates a powerful link between outdoor experience and improved human health. The "green exercise" movement is really taking off. Given this tight interconnection between our bodies and the outdoors, the time has come to speculate about how it all works. For example, we may well imagine that the natural environment stimulates the production of powerful brain chemicals known as outdorphins. This, of course, is a play on the word endorphin, the famous opioid peptides, notable for the "runner's high" and other feel-good effects. I make this comparison only partly in jest; given the incredible subtlety and sophistication of the mind-body system, it would not be far-fetched to suppose the existence of a neuro-hormonal messenger that signaled contact with the natural world.

If such outdorphins did in fact exist, they would be sure to have long-lasting salutary and anabolic effects on the entire mind-body-spirit complex. They would boost cognition, mood, immune function, cardiovascular function, metabolic efficiency, digestion and growth. They would also have a neurotrophic effect, stimulating neurogenesis, synaptogenesis and brain plasticity.

Likewise, we might well speculate about the existence of indorphins. These substances, produced by the brain and body in indoor environments, would have their own particular effects on cognition, mental function and spirit. In small doses, they would sharpen our ability to focus on isolated, individual objects, especially abstract symbols. They would also enhance the function of the brain’s left hemisphere, promoting the development of analytical thought, logic and reason.

However, there’s a catch: indorphins are almost certainly poisonous in large doses. Sustained exposure will produce anxiety, depression and a marked inability to see relationships. Obviously, many people in the modern world suffering from chronic exposure to indorphins and are in need of treatment.

Just as we speculate about indorphins and outdorphins in the body, the time has come to speculate about the difference between indoor and outdoor cognition. Incredibly, this is largely unexplored territory; a quick Internet search returns only a handful of results. But how can this be? Given the incredible sophistication of the human organism and the massive influence of environment on our minds and bodies, it seems safe to assume that there would be a significant, even radical difference between “indoor thinking” and “outdoor thinking.”

After all, we know for certain that cognitive activity is far more than simply the processing done by the brain; the entire body is involved. And there can be no question that the body senses, behaves and responds differently when it’s outdoors. It would be truly bizarre if there wasn’t a difference in the form and content of our thoughts.

The most conspicuous difference between indoor and outdoor settings is our experience of vision. When we’re outdoors, the body naturally scans a wider range of territory. Our hunting and gathering instincts go into action and we make good use of our peripheral vision. While many people understand the basic facts of peripheral vision–its role in motion detection and low-light sensation–few appreciate how big a role it plays in our experience.

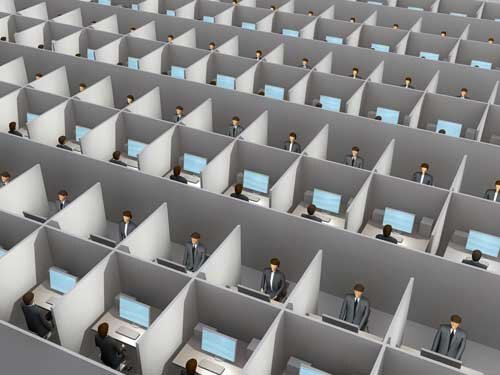

Survival in a mosaic grassland would have required a comprehensive, wide-angle visual scan. But things changed radically as we moved off the grassland into villages and cities; suddenly, our vision shifted from panorama to narrowrama and presumably, our cognition went along for the ride. Our visual-cognitive field narrowed still further with the invention of television and computers. Now, many of us are committed to a single-point visual focus through most of our waking hours. As we spend our days reading, scrolling, focusing and clicking, our peripheral vision becomes increasingly irrelevant and atrophied.

Indoor cognition is about depth, but outdoor cognition is about breadth. Indoor living allows us to specialize, but outdoor living opens up our experience and our minds to greater cognitive vistas. Can it be any wonder that humanity’s great move indoors, beginning some 10,000 years ago, resulted in a concentration of highly focused intelligence, resulting in the spectacular development of modern science and hyper-specialization?

At the same time, we are forced to wonder about our loss of panoramic vistas. As more and more people live their entire lives indoors, our sensitivity to context, environment and relationship declines, just when we need it most. And this, of course, is just one more reason to get out of the office, get out of the house, get out of the car, and go climb a mountain. We need to see the big picture while we still can.