How to do one thing

Agi quod agis “Do what you are doing.”

Hey you!

Put down your phone now and read this.

Yes, you, I’m talking to you!

I know you’re distracted and frantic and in a hurry, you’ve got a million things to do and you need to find out what’s going on and, um…wait… where was I going with this?

Oh, sorry, I got distracted there for a moment...

Now, where was I?

Oh, yeah, I was trying to make a point about multi-tasking and the fact that our entire population is falling into a state of fragmented attention, impulsivity, frenetic activity and superficial engagement with the world. We are in serious trouble.

Seriously.

Experts in neuroscience and performance training are coming to a growing consensus that multi-tasking is an enormous problem that impacts our social relationships, our health and our happiness. It is no exaggeration to call it an epidemic and a behavioral disease. Over the next few years, multi-tasking and electronic devices may well join the ranks of smoking, trans-fats and high-fructose corn syrup consumption in the pantheon of health-negative behaviors of the modern world.

The facts are extremely well established. Every neuroscientist in the world tells us that multi-tasking is a myth. That is, the brain can only attend to one thing at a time. When we try to do two things at once, the brain scrambles as best it can, switching attention rapidly between tasks with lightning speed. But this high-speed switching comes with a cost: Every time we shift the focus of our attention, we must re-engage with the object or process in question, an act that requires psychophysical energy. Not only that, multi-tasking limits our ability to enter into deep engagement with any one thing, which of course limits how well we can perform. In this way, multi-tasking is a lose-lose strategy.

These facts are well-documented, but they are widely ignored and denied by the general public. Apparently, we are simply too distracted to pay attention to the consequences of our distraction. But given the well-established evidence that multi-tasking is an inefficient, even dangerous work and lifestyle, we have to ask, “Why do so many of us persist in doing it?”

The popular answer is completely delusional. “I can get more done” is a cover-up that is demonstrably false. The true motivations run deeper. First, of course, there’s the universal desire for human contact; each flashing light represents the possibility that someone wants to talk to us. This drive towards social relationship is laudable, but there’s a catch: When we give priority to electronic communication, we displace real, authentic human contact, in much the same way that junk food displaces real, nutritional food. In this way, our electronic devices are effectively destroying the opportunity for genuine, face-to-face contact with the people around us.

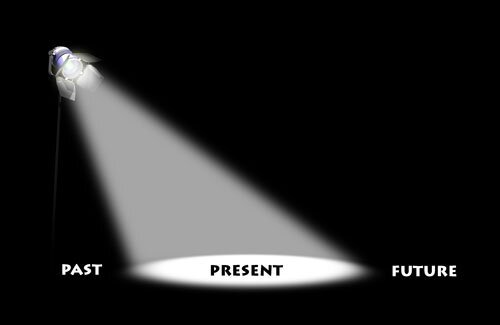

But the real reason we multi-task is more challenging. The fundamental problem, as any meditation teacher will tell us, is that we are uncomfortable in the present moment. There’s something about our lives, our selves, our bodies or our circumstances that makes us uneasy. We’re bored, we’re anxious, we’re afraid, we’re overwhelmed. We can’t just sit in the midst of our predicament; we have to distract ourselves with multiple streams of action and information. In this sense, the electronic device is just another tool of escapism.

Over time, such compulsive running away from the here and now leads to a habitual pattern of addictive flight from even the slightest present-moment discomfort. We experience incipient boredom, anxiety or confusion; instead of feeling these feelings for what they are, we turn directly to the device, flying to the elsewhere and elsewhen, hoping for some better feeling. But of course, this pattern only makes us less adept at living in the present, which ultimately makes us even more anxious and unhappy. It’s a classic vicious cycle.

So what’s the solution? Obviously, we need to change our relationship, not just with our electronic devices, but with our lives as a whole. We need to practice living in the present moment, experiencing our messy, ambiguous and often uncomfortable lives without compulsively reaching for an escape, electronic or otherwise.

This is where physical movement and meditation fit into the picture. Exercise and meditation can only take place in the here and now. When we sit comfortably in one place, or move our bodies vigorously, we stabilize our attention. These activities are pure mono-tasking; a vital practice in a world gone mad with flashing lights, open windows, buzzers and bells. By stabilizing our attention with exercise and meditation, we consolidate our energies into a coherent whole, a process that improves our performance and gives us a greater sense of comfort.

Fortunately, there now seems to be a sea-change sweeping across the professional and popular world. More and more people are beginning to recognize the pathologies of distraction and the benefits of mindfulness meditation. (See the new publication, Mindful.) In the days to come, we’ll see more and more of this at every level. We’ll take increasing pride, not in our ability to split our attention, but in our ability to focus and concentrate on one thing at a time.

So watch your language. To say “I’m great multi-tasker” is an inverted boast, sort of like saying “I’m really good at limping.” A better boast would be to say “I’m a great mono-tasker.” In other words, “I’ve got solid attentional stability. I can live in the here and now without compulsively grasping for an escape. I know how to screen out distractions. I have a powerful ability to avoid multi-tasking.”

Now that would be saying something.