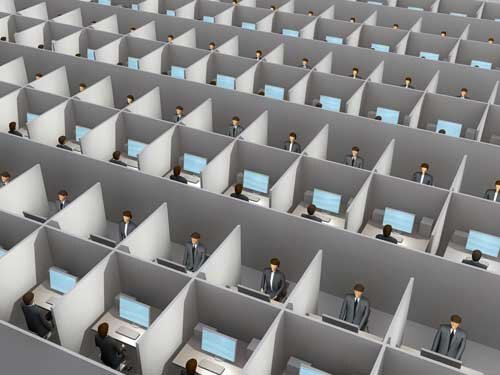

Blinded by walls

“Adopt the pace of nature: her secret is patience.”

Ralph Waldo Emerson

Have you ever been part of a great human migration, a diaspora?

As you ponder this question, you might ask yourself about the great migrations of human history: our epic journeys out of Africa, emigrations out of Europe to the New World or the countless displacements of people fleeing war and environmental catastrophe. But in this wondering, you may well have missed the greatest and most troubling migration in all of human history: our move from the outdoors to the indoors.

Historians don’t even list this outdoor-indoor transition as a great migration, but the description fits. For the vast majority of our time on earth, the wild outdoors was our home. Our bodies, sculpted by thousands of generations in contact with nature, were finely tuned to outdoor conditions. But then, almost overnight, we traded one kind of habitat for another. We picked up our lives en masse and moved indoors.

According to a calculation by New Scientist magazine in February, 2015, the average human lifespan now stands at 78 years, and of that time an average of 70 years is spent inside buildings of one kind or another. In other words, we now spend 89% of our life experience out of contact with nature, insulated by walls, roofs, concrete and glass. In and of itself, this constitutes a tragedy in its own right; by locking ourselves in, we are missing the greatest show on earth. But even worse, we’re also depriving ourselves of an immense body of knowledge and experience that could be improving our health and understanding of how the world really works.

Obviously, indoor habitat has some practical advantages that allow us to do important, creative work. By going indoors, we no longer have to worry about the vagaries of nature: the wind won’t blow our papers around, the rain won’t soak our tools and machines, the heat and cold won’t distract us from our work.

But all this indoor living comes with a substantial downside. In the first place, it distorts our sensory experience. It replaces normal, natural sensation with sights, sounds and textures that are utterly alien to our bodies. Most conspicuously, weak artificial light tweaks the master clock in our brains (the suprachiasmatic nucleus), which scrambles our circadian rhythms and wreaks havoc with other biological clocks that are scattered throughout our bodies. This desynchronizes our physiology and in turn, our health. Not only that, there’s an increasing body of evidence to suggest that low levels of natural light even contribute to a world-wide epidemic of myopia.

But it’s not just physiology. Indoor living takes us out of contact with the world that gives us life. We deprive ourselves of ancient, primal experience that literally makes us who we are. Because we live in boxes, we begin to compartmentalize our knowledge and our imagination. That is to say, we even think differently when we’re indoors. Our ideas, creations and solutions become increasingly linear, analytical, abstract, artificial and yes, dangerous. Walls and roofs make us blind to the very qualities that might well keep us whole, sane and healthy.

The obvious cure for our indoor incarceration is to simply spend more time going outside. In fact, an increasing number of public health officials and trainers are trying to persuade people to do just that. Increasingly frustrated with sophisticated health recommendations for diet and exercise, health advocates now plead with people to simply go outside for a few minutes each day. Surely that can’t be too much to ask.

But there’s more to this challenge than simply stepping outside for a break in the midst of a crushing indoor work day. What we really need is to immerse ourselves in the outdoor experience. Sure, many of us do in fact go outside, but we don’t really inhabit the outdoor world. We bring our phones along to keep our minds busy and we talk shop every step of the way. In effect, we don’t really go outside at all; we simply bring the indoors with us.

This is something that I’ve noticed when hiking the trails outside Seattle, Washington. On the weekends there are hundreds of people on the trails and it’s impossible to miss hearing their conversations. In the aggregate, they often sound like this:

“…posted on Facebook… and then I logged in…interface…venture capital...the download took forever…my cell phone…texted me…HTML…website...Android…so I Googled it…I’ve got this new app…stock options…new version…Macbook…you can get it on iTunes…network…”

And on it goes, all the way up the mountain. It’s as if no one is really, truly on the trail. Even on the summit, the conversation is all the same techno-corporate rap of the working day. No one seems to notice the plants, weather, terrain, textures, colors, birds or animals. No one stops talking. No one is truly outside.

To have an authentic outdoor experience, we have to go all the way out. That means leaving the indoor language indoors. Just as walls make us blind, a Swahili saying tells us that “The tongue makes us deaf.” What we need is to re-inhabit our habitat. This means immersing ourselves in nature, moving and thinking at the speed of habitat. So slow down, go outside, pay attention to the qualities of nature and above all, stop talking and start listening.

Note: Exuberant Animal will be in London, June 20-21, offering a workshop: "Health, Performance and the Human Predicament." Sign up information: click here.

For books by Frank Forencich and more information about Exuberant Animal, visit the website